The loudness war has been going on for some time with musicians, producers and record companies over the past few decades mastering and releasing their records with ever increasing volume and compression. In the days of vinyl there was a physical limit to how loud you could press a record before the needle would be unable to play it – the advent of Compact Discs however changed that. Whilst they boasted a greater dynamic range than vinyl they also defined a maximum peak ampltitude. Through some science and a bunch of signal processing, record engineers could thus push the overall volume of a track so that it became louder throughout, often hitting peak and compressing the dynamic range of the record. The long and short of this is that modern records nearly all tend to have dynamic range compression applied and the result is a loss of sound quality in the form of distortion and clipping.

Why do record companies do this? A popular perception (misconception?) is that the louder a record sounds – the better it sounds – and hence the more likely someone hearing it in the record store or over the radio is to buy it.

Note the mediums over which most people traditionally hear new music – inside record stores, over the radio, in the coffee shop, on their phones, tablets and notebooks – none of these mediums are known for high fidelity listening and their poor quality speakers tend to mask the compression in the music. As a result loud sells.

So if that new track by The Killers sounds good to you playing on the cheap speakers at your local coffee shop just wait until you hear the Muse single coming up – it’s probably louder and in a noisy coffee shop will sound better.

The problem arises when you listen to that record on your nice, shiny headphones or your stereo at home – in a quiet environment, with good audio equipment those distorted, normalised tracks are going to sound noisy, fatiguing and to be perfectly blunt – a bit crap.

A backlash from consumers and high end audio equipment manufacturers was bound to happen with the demand for high quality, well mastered records ever increasing. Companies like HDtracks, naimlabel and LINN Records to name a few, stepped in to fill the gap. Offering not only well mastered tracks they also boast a higher resolution than CD can provide, with the quality up to 24-bits and 192kHz. One thing which needs to be stressed however is that mastering matters – in fact it matters more than how much fidelity a record has: A poorly mastered 24-bit 192kHz record is not going to sound any better than a well mastered 16-bit 44.1kHz CD. In fact if it’s very poorly mastered it will almost certainly sound worse than an MP3 rip of the CD.

Take Elton John’s self titled album for example. Here it began life in 1970 on vinyl. No sign of clipping or compression here:

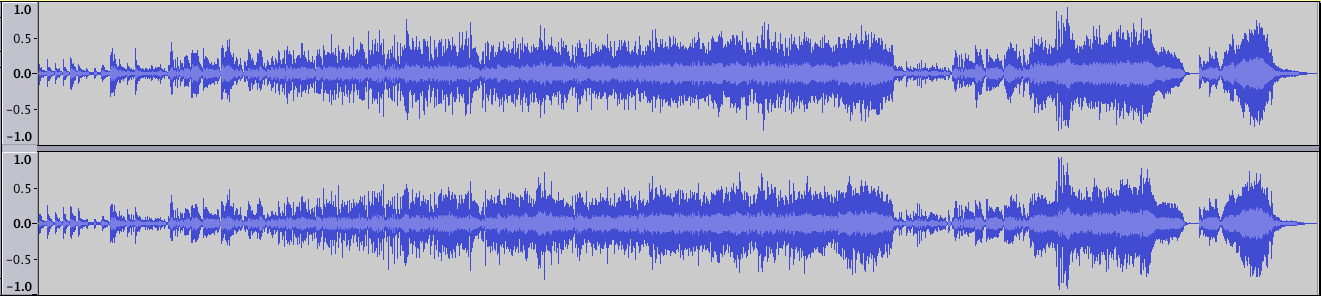

In 1985 it was released on CD, again with no discernible compression:

In 1995 it was re-released as a Remastered Edition on CD. You can see the track is louder but it’s just about acceptable:

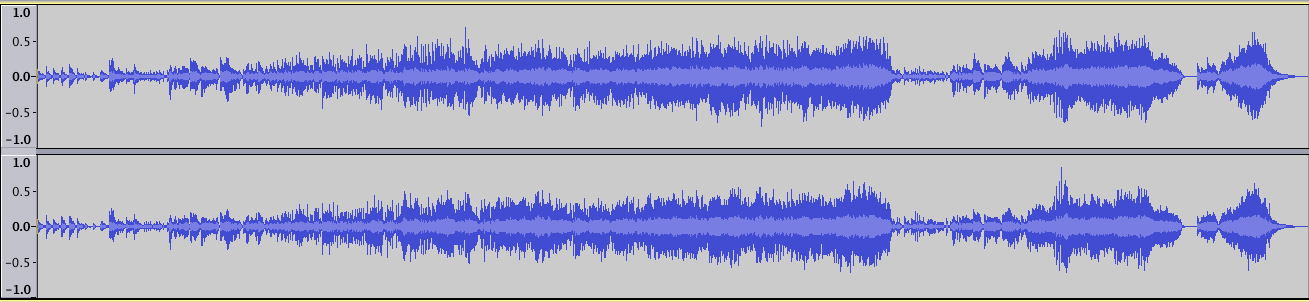

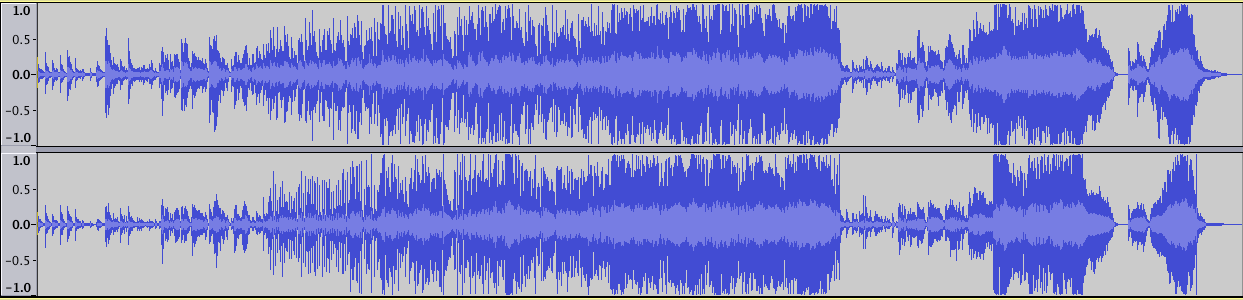

In 2008 it was again re-released as a Deluxe Edition CD. As expected for a modern release, it’s been made loud and sounds compressed and fatiguing as a result:

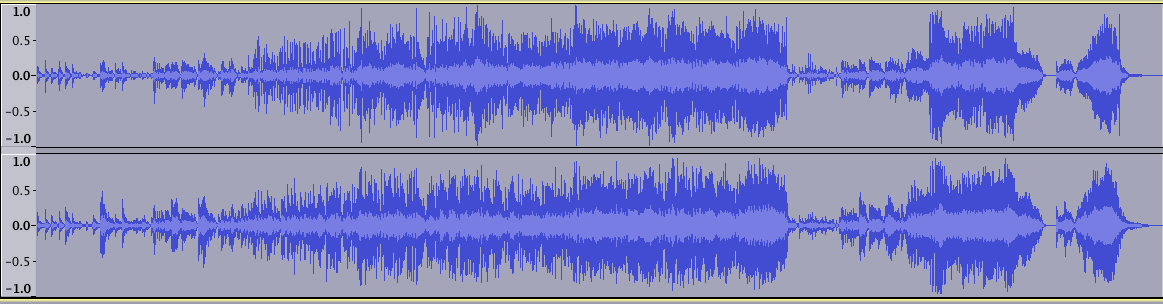

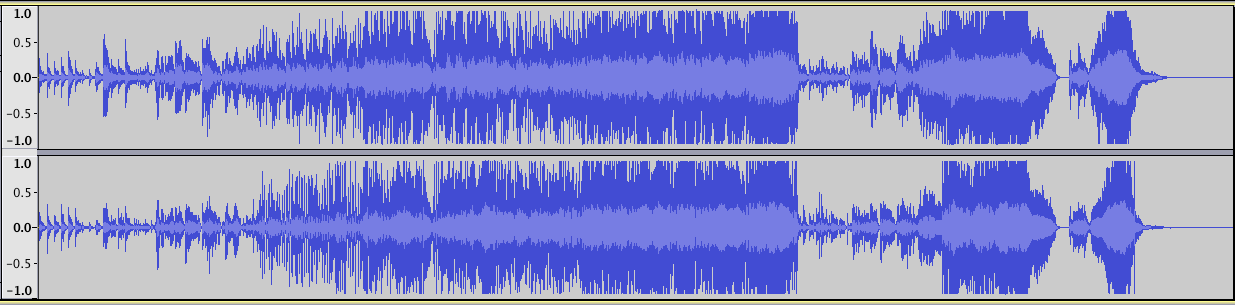

Finally Elton John’s album appears on HDtracks in high definition 24-bit 96kHz. It should offer the best sound quality but to take advantage of the vast dynamic range of those 24-bits it will need to be mastered properly. Here we can see that this is definitely not the case. In fact it suffers from more dynamic range compression than the 2008 CD release:

The HDtracks edition should offer the best sound quality – after all it is 24-bit 96kHz and comes from a store which aims to provide high end audio tracks. Sadly it suffers from bad mastering. The result is a lot of clipping and excessive loudness and consequently it sounds worse than the older, less compressed editions.

So what can we surmise from this? Put simply that despite the much touted quality of 24-bit music there’s no certainty that the HD version of the album you’re buying is also mastered properly and free from excessive normalisation and distortion. For those looking to upgrade their album collection it’s clear that there’s no guarantee your new, 24-bit purchases will sound better. This is a great pity since technically the new high definition audio formats offer higher quality than has ever been possible – if only the studios, record producers and artists would oblige. Until then for those seeking quality HD audio tracks it’s a crapshoot.